Everyone wants to get the most out of the limited amount of time they get to spend alone at the keyboard. At any point in your development as a keyboard player, there are dozens if not hundreds of different directions you could choose to explore. How do you decide which way to go to maximize that precious practice time?

The more you understand about the relationships that musical elements have to one another, the easier it will be for you to spend your practice time learning the things that will be the most useful to you. When you begin to see how one chord form can be applied to keys and contexts you may have overlooked, you can then work on multiple elements simultaneously. And the more you understand about the relationships among elements, the easier it is to apply them to create new sounds, voicings, compositions, and ways of soloing.

For instance, I can remember a time when I didn’t know that a minor 7th chord could be thought of as occurring on the 5th degree of a dominant 7th scale. Making this realization opened my eyes to the fact that chords come from specific points on scales, and that I didn’t need to think of a different scale to solo over each chord in a tune. It also made me realize that there was something larger going on, and that music was about relationships. Part of our work as musicians is to discover how things are related to each other.

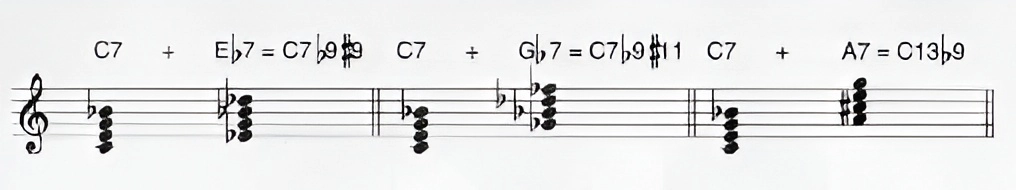

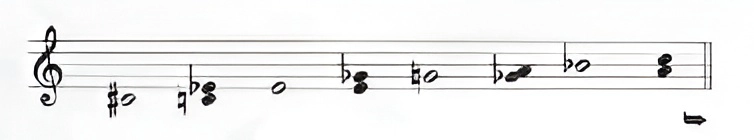

To begin with, take a look at The Dominant Species (click the link) to get a basic understanding of where I think musical elements come from. In essence, I think of chords as being derived from dominant scales, each of which is in turn related to three other dominant scales and the chords generated by them. Each set of four dominant chords is related by virtue of having been generated from a single diminished 7th chord. As you can see from the side bar (click the link), there are three diminished 7th chords; each generates four dominant 7th chords. That means we’re covering all twelve keys.

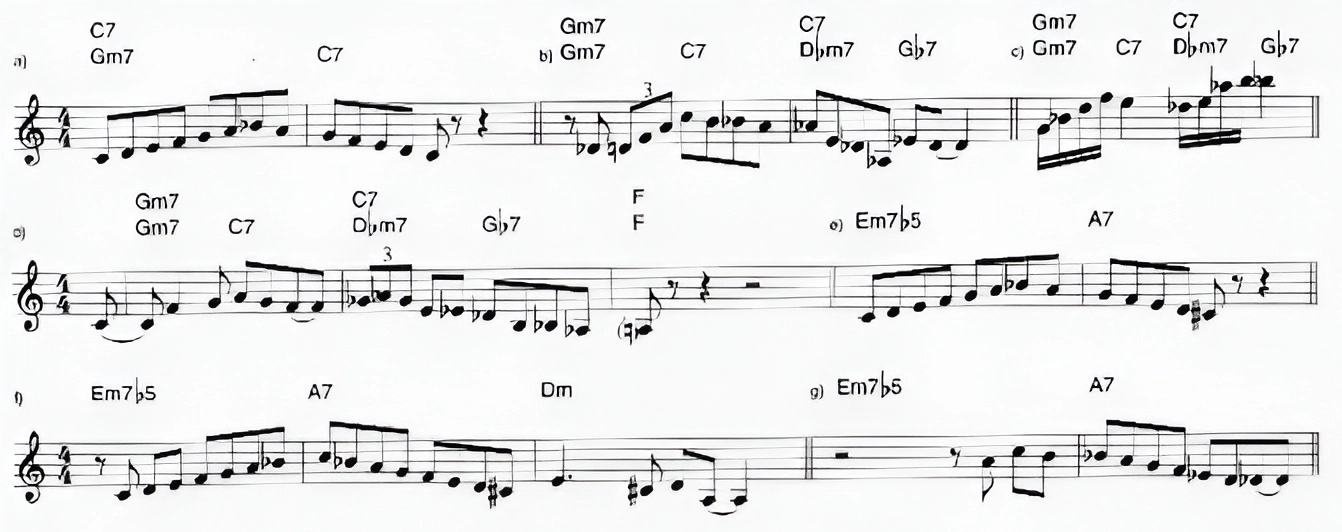

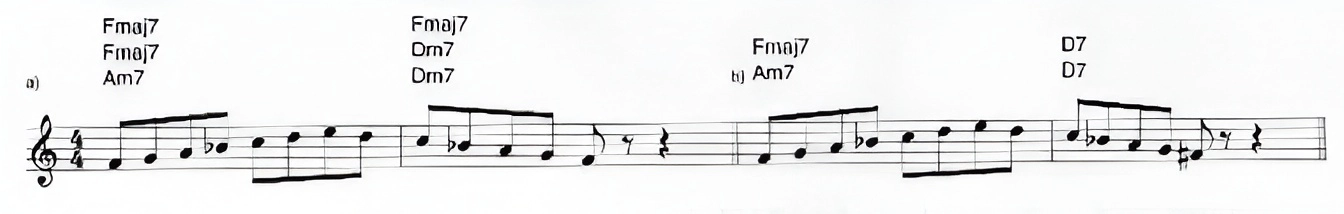

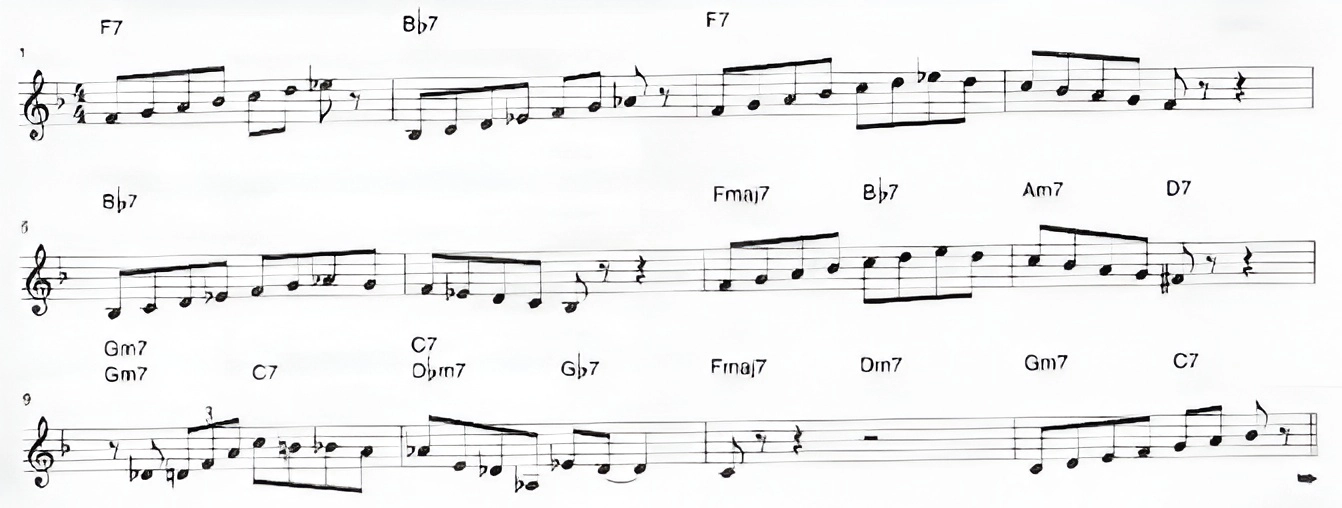

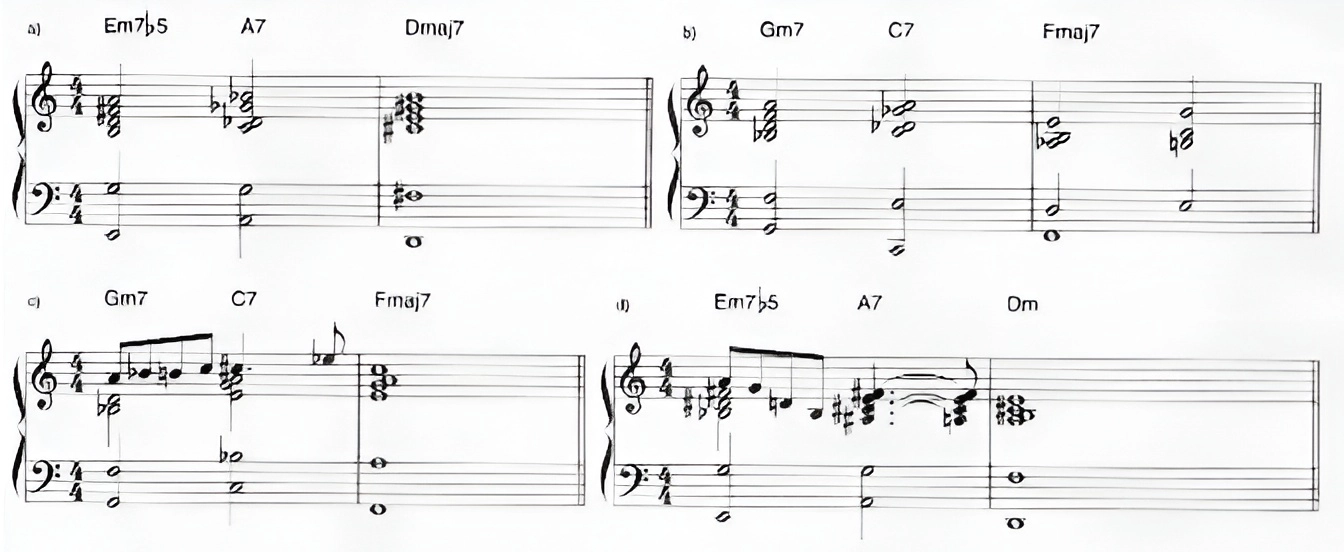

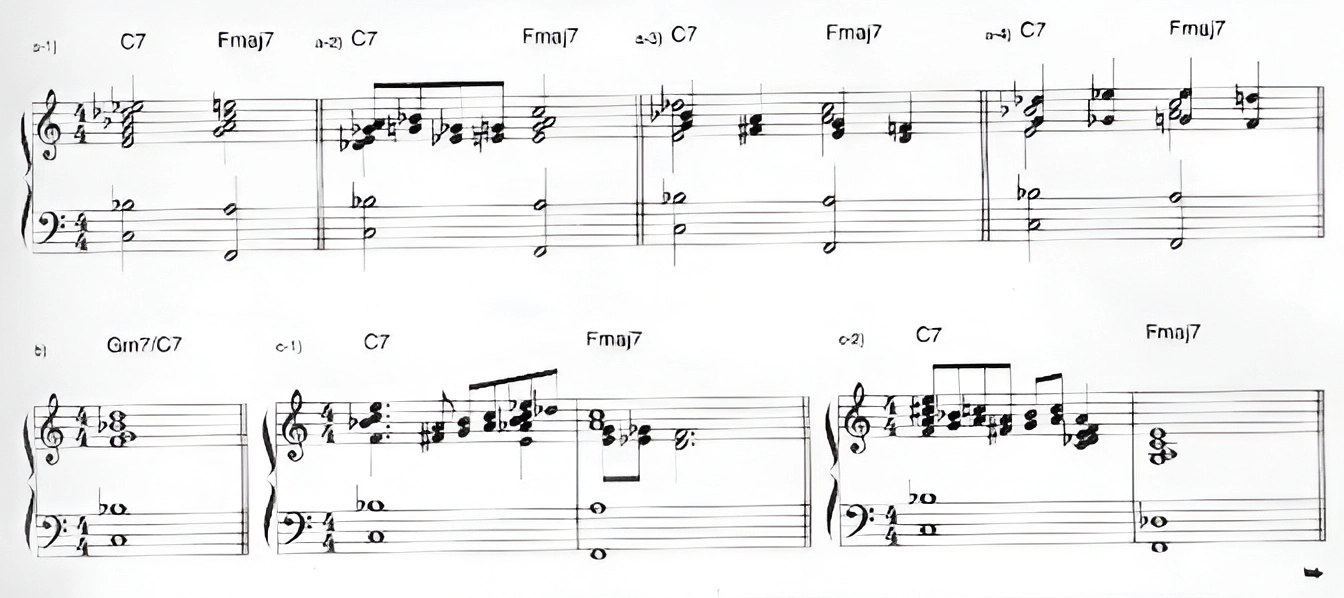

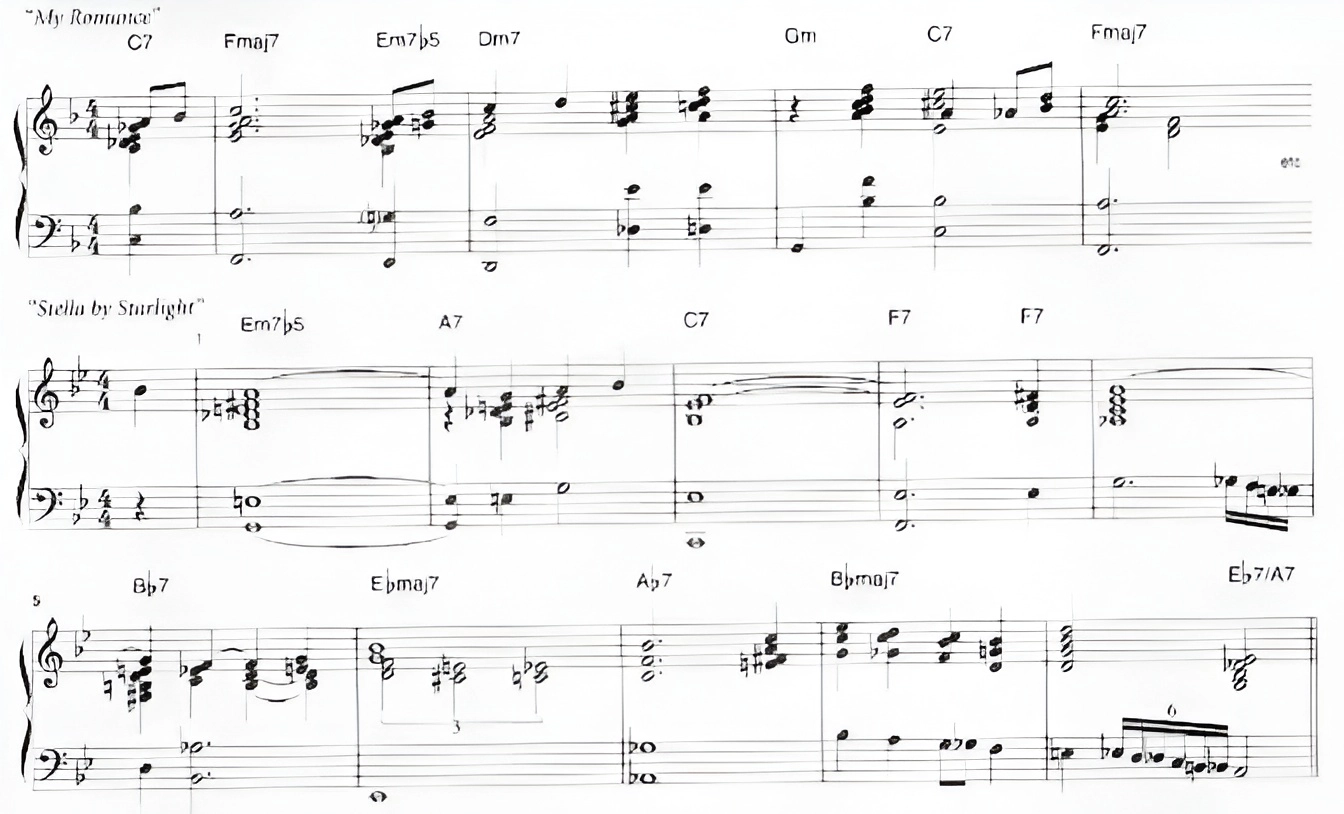

In the examples, I’ve chosen chord progressions that are most commonly found in standard jazz tunes. By structuring your practise time along the lines of what I’ve described in Figure 1, you can begin to experience the close relationship between the dominant 7th chords and scales, you learn to apply them to real-world progressions, and you cover all twelve keys without having to resort to boring Circle of Fifth progressions. You’ll be practising scales with more of an awareness of a larger musical context. And the various ways you’ll find to connect the pairs of scales together wil become part of your own bag of musical tricks. Example 1 shows some ideas on running pairs of dominant scales together; Example 2 suggests how to do this thinking in terms of the major scale. Note that going up and down a scale is a two-bar phase. The octave is omitted so you can stay in time.

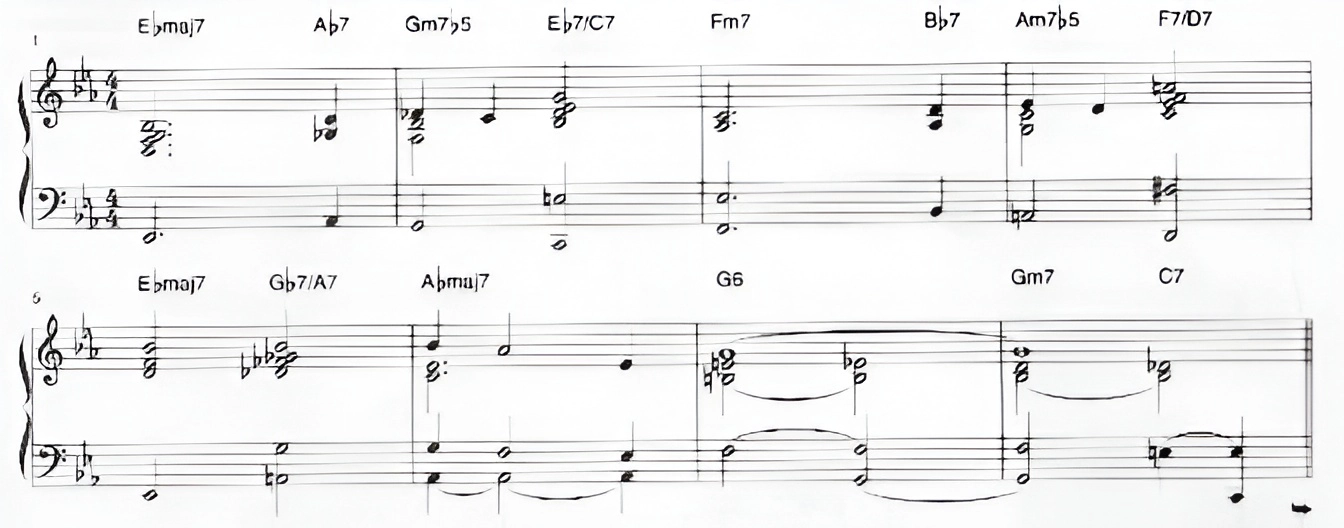

The rest of the examples explore the ways that dominant 7th and 6th chords are related, how they work as dominant substitutions for each other, and how they can be combined and added to – all within the context of their shared relationships. The final example, Example 10, shows you how to apply your new skills to tunes.

I hope you’ll find this idea of the underlying structure of scales and chords to be helpful in your practice time. But most important , I hope that it helps you discover new ways of creating sounds that you can use in your own music.

Howard Rees